![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() Sources

Sources

![]() Galileo’s Balance

Galileo’s Balance

| Back to . . . |

This section . . .

|

|

In 1586 at the age of 22, Galileo (1564-1642) wrote a short treatise entitled La Bilancetta (“The Little Balance”). He was skeptical of Vitruvius’s account of how Archimedes determined the fraud in Hiero's crown and in this treatise presented his own theory based on Archimedes’ Law of the Lever and Law of Buoyancy. He also included a description of a hydrostatic balance that determined the precise composition of an alloy of two metals.

Below is the complete text of Galileo’s treatise in the original Italian together with a modern English translation. |

|

|

THE LITTLE BALANCE Galileo Galilei Just as it is well known to anyone who takes the care to read ancient authors that Archimedes discovered the jeweler’s theft in Hiero’s crown, it seems to me the method which this great man must have followed in this discovery has up to now remained unknown. Some authors have written that he proceeded by immersing the crown in water, having previously and separately immersed equal amounts [in weight] of very pure gold and silver, and, from the differences in their making the water rise or spill over, he came to recognize the mixture of gold and silver of which the crown was made. But this seems, so to say, a crude thing, far from scientific precision; and it will seem even more so to those who have read and understood the very subtle inventions of this divine man in his own writings; from which one most clearly realizes how inferior all other minds are to Archimedes’s and what small hope is left to anyone of ever discovering things similar to his [discoveries]. I may well believe that, a rumor having spread that Archimedes had discovered the said theft by means of water, some author of that time may have then left a written record of this fact; and that the same [author], in order to add something to the little that he had heard, may have said that Archimedes used the water in that way which was universally believed. But my knowing that this way was altogether false and lacking that precision which is needed in mathematical questions made me think several times how, by means of water, one could exactly determine the mixture of two metals. And at last, after having carefully gone over all that Archimedes demonstrates in his books On Floating Bodies and Equilibrium, a method came to my mind which very accurately solves our problem. I think it probable that this method is the same that Archimedes followed, since, besides being very accurate, it is based on demonstrations found by Archimedes himself. |

LA BILANCETTA Galileu Galilei Sì come è assai noto a chi di leggere gli antichi scrittori cura si prende, avere Archimede trovato il furto dell'orefice nella corona d'oro di Ierone, così parmi esser stato sin ora ignoto il modo che sì grand'uomo usar dovesse in tale ritrovamento: atteso che il credere che procedesse, come da alcuni è scritto, co 'l mettere tal corona dentro a l'aqqua, avendovi prima posto altrettanto di oro purissimo e di argento separati, e che dalle differenze del far più o meno ricrescere o traboccare l'aqqua venisse in cognizione della mistione dell'oro con l'argento, di che tal corona era composta, par cosa, per così dirla, molto grossa e lontana dall'esquisitezza; e vie più parrà a quelli che le sottilissime invenzioni di sì divino uomo tra le memorie di lui aranno lette ed intese, dalle quali pur troppo chiaramente si comprende, quando tutti gli altri ingegni a quello di Archimede siano inferiori, e quanta poca speranza possa restare a qualsisia di mai poter ritrovare cose a quelle di esso simiglianti. Ben crederò io che, spargendosi la fama dell'aver Archimede ritrovato tal furto co 'l mezo dell'aqqua, fosse poi da qualche scrittore di quei tempi lasciata memoria di tal fatto; e che il medesimo, per aggiugner qualche cosa a quel poco che per fama avea inteso, dicesse Archimede essersi servito dell'aqqua nel modo che poi è stato dall'universal creduto. Ma il conoscer io che tal modo era in tutto fallace e privo di quella esattezza che si richiede nelle cose matematiche, mi ha più volte fatto pensare in qual maniera, co 'l mezo dell'aqqua, si potesse esquisitamente ritrovare la mistione di due metalli; e finalmente, dopo aver con diligenza riveduto quello che Archimede dimostra nei suoi libri Delle cose che stanno nell'aqqua ed in quelli Delle cose che pesano ugualmente, mi è venuto in mente un modo che esquisitissimamente risolve il nostro quesito: il qual modo crederò io esser l'istesso che usasse Archimede, atteso che, oltre all'esser esattissimo, depende ancora da dimostrazioni ritrovate dal medesimo Archimede. |

|

This method consists in using a balance whose construction and use we shall presently explain, after having expounded what is needed to understand it. One must first know that solid bodies that sink in water weigh in water so much less than in air as is the weight in air of a volume of water equal to that of the body. This [principle] was demonstrated by Archimedes, but because his demonstration is very laborious I shall leave it aside, so as not to take too much time, and I shall demonstrate it by other means. Let us suppose, for instance, that a gold ball is immersed in water. If the ball were made of water it would have no weight at all because water inside water neither rises nor sinks. It is then clear that in water our gold ball weighs the amount by which the weight of the gold [in air] is greater than in water. The same can be said of other metals. And because metals are of different [specific] gravity, their weight in water will decrease in different proportions. Let us assume, for instance, that gold weighs twenty times as much as water; it is evident from what we said that gold will weight less in water than in air by a twentieth of its total weight [in air]. Let us now suppose that silver, which is less heavy than gold, weighs twelve times as much as water; if silver is weighed in water its weight will decrease by a twelfth. Thus the weight of gold in water decreases less than that of silver, since the first decreases by a twentieth, the second by a twelfth. |

Il modo è co 'l mezo di una bilancia, la cui fabbrica; ed uso qui apresso sarà posto, dopo che si averà dichiarato quanto a tale intelligenza è necessario. Devesi dunque prima sapere, che i corpi solidi che nell'aqqua vanno al fondo, pesano meno dell'aqqua che nell'aria tanto, quant'è nell'aria la gravità di tant'aqqua in mole quant'è esso solido: il che da Archimede è stato dimostrato; ma perché la sua dimostrazione è assai mediata, per non avere a procedere troppo in lungo, lasciandola da parte, con altri mezi lo dichiarerò. Consideriamo, dunque, che mettendo, per esempio, nell'aqqua una palla di oro, se tal palla fosse di aqqua, non peserebbe nulla, perché l'aqqua nell'aqqua non si muove in giù o in su. Resta dunque che tal [palla] di oro pesi nel[l'aqqua] quel tanto, in che la gravità dell'oro supera la gravità dell'aqqua; ed il simile si deve intendere de gli altri metalli: e perché i metalli son diversi tra di loro in gravità, secondo diverse proporzioni scemerà la lor gravità nell'aqqua. Come, per essempio, poniamo che l'oro pesi venti volte più dell'aqqua; è manifesto dalle cose dette, che l'oro peserà meno nell'aqqua che nell'aria la vigesima parte di tutta la sua gravità: supponiamo ora che l'argento, per esser men grave dell'oro, pesi 12 volte più che l'aqqua; questo, pesato nell'aqqua, scemerà in graveza per la duodecima parte: adunque meno scema nell'aqqua la gravità dell'oro che quella dell'argento, atteso che quella scema per un ventesimo e questa per un duodecimo. |

| |

|

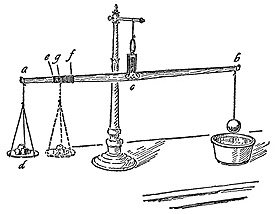

Let us suspend a [piece of] metal on [one arm of] a scale of great precision, and on the other arm a counterpoise weighing as much as the piece of metal in air. If we now immerse the metal in water and leave the counterpoise in air, we must bring the said counterpoise closer to the point of suspension [of the balance beam] in order to balance the metal. Let, for instance, ab be the balance [beam] and c its point of suspension; let a piece of some metal be suspended at b and counterbalanced by the weight d. If we immerse the weight b in water the weight d at a in the air will weigh more [than b in water], and to make it weigh the same we should bring it closer to the point of suspension c, for instance to e. As many times as the distance ac will be greater than the distance ae, that many times will the metal weigh more than water. |

Se dunque in una bilancia esquisita noi appenderemo un metallo, e dall'altro braccio un contrapeso che pesi ugualmente co 'l detto metallo in aria; se poi tufferemo il metallo nell'aqqua, lasciando il contrapeso in aria; acciò detto contrapeso equivaglia al metallo, bisognerà ritirarlo verso il perpendicolo. Come, per essempio, sia la bilancia ab, il cui perpendicolo c; ed una massa di qualche metallo sia appesa in b, contrapesata dal peso d. Mettendo il peso b nell'aqqua, il peso d in a peserebbe più: però, acciò che pesasse ugualmente, bisognerebbe ritirarlo verso il perpendicolo c, come, v.g, in e; e quante volte la distanza ca supererà la ae, tante volte il metallo peserà più che l'aqqua. |

|

Let us then assume that weight b is gold and that when this is weighed in water, the counterpoise goes back to e; then we do the same with very pure silver and when we weigh it in water its counterpoise goes in f. This point will be closer to c [than is e], as the experiment shows us, because silver is lighter than gold. The difference between the distance af and the distance ae will be the same as the difference between the [specific] gravity of gold and that of silver. But if we shall have a mixture of gold and silver it is clear that because this mixture is in part silver it will weigh less than pure gold, and because it is in part gold it will weigh more than pure silver. If therefore we weigh it in air first, and if then we want the same counterpoise to balance it when immersed in water, we shall have to shift said counterpoise closer to the point of suspension c than the point e, which is the mark for gold, and farther than f, which is the mark of pure silver, and therefore will fall between the marks e and f. From the proposition in which the distance ef will be divided we shall accurately obtain the proportion of the two metals composing the mixture. So, for instance, let us assume that the mixture of gold and silver is at b, balanced in air by d, and that his counterweight goes to g when the mixture is immersed in water. I now say that the gold and silver that compose the mixture are in the same proportion as the distances fg and ge. We must however note that the distance gf, ending in the mark for silver, will show the amount of gold, and the distance ge ending in the mark for gold will indicate the quantity of silver; so that, if fg will be twice ge, the said mixture will be of two [parts] of gold and one of silver. And thus, proceeding in this same order in the analysis of other mixtures, we shall accurately determine the quantities of the [component] simple metals. |

Poniamo dunque che il peso in b sia oro, e che pesato nell'aqqua torni il contrapeso d in e; e poi, facendo il medesimo dell'argento finissimo, che il suo contrapeso, quando si peserà poi nell'aqqua, torni in f: il qual punto sarà più vicino al punto c, sì come l'esperienza ne mostra, per esser l'argento men grave dell'oro; e la differenza che è dalla distanza af alla distanza ae sarà la medesima che la differenza tra la gravità dell'oro e quella de l'argento. Ma se noi aremo un misto di oro e di argento, è chiaro che, per participare di argento, peserà meno che l'oro puro, e, per participar di oro, peserà più che il puro argento: e però, pesato in aria, e volendo che il medesimo contrapeso lo contrapesi quando tal misto sarà tuffato nell'aqqua, sarà di mestiero ritirar detto contrapeso più verso il perpendicolo c che non è il punto e, il quale è il termine dell'oro, e medesimamente più lontano dal c che non è l'f, il quale è il termine dell'argento puro; però cascherà tra i termini e, f, e dalla proporzione nella quale verrà divisa la distanza ef si averà esquisitamente la proporzione dei due metalli, che tal misto compongono. Come, per esempio, intendiamo che il misto di oro ed argento sia in b, contrapesato in aria da d; il qual contrapeso, quando il misto sia posto nell'aqqua, ritorni in g: dico ora che l'oro e l'argento, che compongono tal misto, sono tra di loro nella medesima proporzione che le distanze fg, ge. Ma ci è da avvertire che la distanza gf, terminata nel segno dell'argento, ci denoterà la quantità dell'oro, e la distanza ge, terminata nel segno dell'oro, ci dimostrerà la quantità dell'argento: di maniera che se fg tornerà doppia di ge, il tal misto sarà due d'oro ed uno di argento. E col medesimo ordine procedendo nell'esamine di altri misti, si troverà esquisitamente la quantità dei semplici metalli. |

|

To construct this balance, take a [wooden] bar at least two braccia long―the longer the bar, the more accurate the instrument [2 braccia ≅ 117 centimeters]. Suspend it in its middle point; then adjust the arms so that they are in equilibrium, by thinning out whichever happens to be heavier; and on one of the arms mark the points where the counterpoises of the pure metals go when these are weighed in water, being careful to weigh the purest metals that can be found. Having done this, we must still find a way by which easily to obtain the proportions in which the distances between the marks for the pure metals are divided by the marks for the mixtures. This, in my opinion, may be achieved in the following way. |

Per fabricar dunque la bilancia, piglisi un regolo lungo almeno due braccia, e quanto più sarà lungo più sarà esatto l'istrumento; e dividasi nel mezo, dove si ponga il perpendicolo; poi si aggiustino le braccia che stiano nell'equilibrio, con l'assottigliare quello che pesasse più; e sopra l'uno delle braccia si notino i termini [dove ritor]nano i contrapesi de i metalli semplici quando saranno pesati nell'aqqua, avvertendo di pesare i metalli più puri che si trovino. Fatto che sarà questo, resta a ritrovar modo col quale si possa con facilità aver la proporzione, [secondo la quale] le distanze tra i termini de i metalli puri verra[nno] divise da i segni de i misti. Il che, al mio giudizio, si conseguirà in questo modo: |

|

On the marks for the pure metals wind a single turn of very fine wire, and around the intervals between marks wind a brass wire, also very fine: these distances will be divided in many very small parts. Thus, for instance, on the marks e, f I wind only two turns of steel wire (and I do this to distinguish them from brass); and then I go on filling up the entire space between e and f by winding on it a very find brass wire, which will divide the space ef into many small equal part. When then I shall want to know the proportion between fg and ge I shall count the number of turns in fg and the number of turns in ge, and I shall find, for instance, that the turns in fg are 40 and the turns in ge 21, I shall say that in the mixture there are 40 parts of gold and 21 of silver. |

Sopra i termini de i metalli semplici avvolgasi un sol filo di corda di acciaio sottilissima; ed intorno agli intervalli, che tra i termini rimangono, avvolgasi un filo di ottone pur sottilissimo; e verranno tali distanze divise in molte particelle uguali. Come, per essempio, sopra i termini e, f avvolgo 2 fili solo di acciaio (e questo per distinguerli dall'ottone); e poi vo riempiendo tutto lo spazio tra e, f con l'avvolgervi un filo sottilissimo di ottone, il quale mi dividerà lo spazio ef in molte particelle uguali; poi, quando io vorrò sapere la proporzione che è tra fg e ge, conterò i fili fg ed i fili ge, e, trovando i fili fg esser 40 ed i ge esser, per essempio, 21, dirò nel misto esser 40 di oro e 21 di argento. |

|

Here we must warn that a difficulty in counting arises: Since the wires are very fine, as is needed for precision, it is not possible to count them visually, because the eye is dazzled by such small spaces. To count them easily, therefore, take a most sharp stiletto and pass it slowly over the said wires. Thus, partly through our hearing, and partly through our hand feeling an obstacle at each turn of wire, we shall easily count said turns. And from their number, as I said before, we shall obtain the precise quantity of pure metals of which the mixture is composed. Note, however, that these metals are in inverse proportion to the distances: Thus, for instance, in a mixture of gold and silver the coils toward the mark for silver will give the quantity of gold, and the coils toward the mark for gold will indicate the quantity of silver; and the same is valid for other mixtures. |

Ma qui è da avvertire che nasce una difficultà nel contare: però che, per essere quei fili sottilissimi, come si richiede all'esquisitezza, non è possibile con la vista numerarli, però che tra sì piccoli spazii si abbaglia l'occhio. Adunque, per numerargli con facilità, piglisi uno stiletto acutissimo, col quale si vada adagio adagio discorrendo sopra detti fili; ché così, parte mediante l'udito, parte mediante il ritrovar la mano ad ogni filo l'impedimento, verranno con facilità detti fili numerati: dal numero de i quali, come ho detto di sopra, si averà l'esquisita quantità de i semplici, de' quali è il misto composto. Avvertendo però, che i semplici risponderanno contrariamente alle distanze: come, per esempio, in un misto d'oro e d'argento, i fili che saranno verso il termine dell'argento ci daranno la quantità dell'oro, e quelli che saranno verso 'l termine dell'oro ci dimostreranno la quantità dell'argento; ed il medesimo intendasi degli altri misti. |

The English translation and top right illustration are from:

Galileo and the Scientific Revolution

by Laura Fermi and Gilberto Bernardini

(Translated with the assistance of Cyril Stanley Smith)

Basic Books, Inc., New York, 1961

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-7486Republished by Dover Publications, 2003

ISBN: 0486432262

The Italian text and middle diagram are from:

Opera di Galileo Galilei

Edited by Franz Brunetti

Unione tipografico-editrice torinese (UTET)

Torino, 1980

ISBN: 8802034575