|

Abstract: Many species of fish and birds travel in groups, yet the role of fluid-mediated interactions in schools and flocks is not fully understood. Previous fluid-dynamical models of these collective behaviors assume that all individuals flap identically, whereas animal groups involve variations across members as well as active modifications of wing or fin motions. To study the roles of flapping kinematics and flow interactions, we design a minimal robotic “school” of two hydrofoils swimming in tandem. The flapping kinematics of each foil are independently prescribed and systematically varied, while the forward swimming motions are free and result from the fluid forces. Surprisingly, a pair of uncoordinated foils with dissimilar kinematics can swim together cohesively—without separating or colliding—due to the interaction of the follower with the wake left by the leader. For equal flapping frequencies, the follower experiences stable positions in the leader’s wake, with locations that can be controlled by flapping amplitude and phase. Further, a follower with lower flapping speed can defy expectation and keep up with the leader, whereas a faster-flapping follower can be buffered from collision and oscillate in the leader’s wake. We formulate a reduced-order model which produces remarkable agreement with all experimentally observed modes by relating the follower’s thrust to its flapping speed relative to the wake flow. These results show how flapping kinematics can be used to control locomotion within wakes, and that flow interactions provide a mechanism which promotes group cohesion. |

Coverage:

|

Abstract: Aeronautical studies have shown that subtle changes in aerofoil shape substantially alter aerodynamic forces during fixed-wing flight. The link between shape and performance for flapping locomotion involves distinct mechanisms associated with the complex flows and unsteady motions of an air- or hydro-foil. Here, we use an evolutionary scheme to modify the cross-sectional shape and iteratively improve the speed of three-dimensional printed heaving foils in forward flight. In this algorithmic-experimental method, ‘genes’ are mathematical parameters that define the shape, ‘breeding’ is the combination of genes from parent wings to form a daughter, and a wing's measured speed is its ‘fitness’ that dictates its likelihood of breeding. Repeated over many generations, this process automatically discovers a fastest foil whose cross-section resembles a slender teardrop. We conduct an analysis that uses the larger population to identify what features of this shape are most critical, implicating slenderness, location of maximum thickness and fore-aft asymmetries in edge sharpness or bluntness. This analysis also reveals a tendency towards extremely thin and cusp-like trailing edges. These findings demonstrate artificial evolution in laboratory experiments as a successful strategy for tailoring shape to improve propulsive performance. Such a method could be used in related optimization problems, such as tuning kinematics or flexibility for flapping propulsion, and for flow–structure interactions more generally. |

Coverage:

|

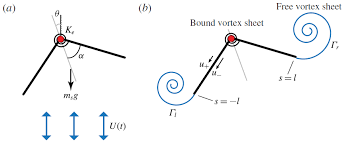

Abstract: We explore the rotational stability of hovering flight in an idealized two-dimensional model. Our model is motivated by an experimental pyramid-shaped object (Weathers et al., J. Fluid Mech, vol. 650, 2010, pp. 415–425; Liu et al., Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 108, 2012, 068103) and a computational Λ-shaped analogue Huang et al., Phys. Fluids, vol. 27 (6), 2015, 061706; Huang et al., J. Fluid Mech., vol. 804, 2016, pp. 531–549) hovering passively in oscillating airflows; both systems have been shown to maintain rotational balance during free flight. Here, we attach the Λ -shaped flyer at its apex in oscillating flow, allowing it to rotate freely akin to a pendulum. We use computational vortex sheet methods and we develop a quasi-steady point-force model to analyse the rotational dynamics of the flyer. We find that the flyer exhibits stable concave-down and concave-up behaviour. Importantly, the down and up configurations are bistable and co-exist for a range of background flow properties. We explain the aerodynamic origin of this bistability and compare it to the inertia-induced stability of an inverted pendulum oscillating at its base. We then allow the flyer to flap passively by introducing a rotational spring at its apex. For stiff springs, flexibility diminishes upward stability but as stiffness decreases, a new transition to upward stability is induced by flapping. We conclude by commenting on the implications of these findings for biological and man-made aircraft. |

|

Abstract: Natural sculpting processes such as erosion or dissolution often yield universal shapes that bear no imprint or memory of the initial conditions. Here we conduct laboratory experiments aimed at assessing the shape dynamics and role of memory for the simple case of a dissolvable boundary immersed in a fluid. Though no external flow is imposed, dissolution and consequent density differences lead to gravitational convective flows that in turn strongly affect local dissolving rates and shape changes, and we identify two distinct behaviors. A flat boundary dissolving from its lower surface tends to retain its overall shape (an example of near perfect memory) while bearing small-scale pits that reflect complex near-body flows. A boundary dissolving from its upper surface tends to erase its initial shape and form an upward spike structure that sharpens indefinitely. We propose an explanation for these different outcomes based on observations of the coupled shape dynamics, concentration fields, and flows. |

Coverage:

|

Abstract: We study how a suspended liquid film is deformed by an external flow en route to forming a bubble through experiments and a model. We identify a family of nonminimal but stable equilibrium shapes for flow speeds up to a critical value beyond which the film inflates unstably, and the model accounts for the observed nonlinear deformations and forces. A saddle-node or fold bifurcation in the solution diagram suggests that bubble formation at high speeds results from the loss of equilibrium and at low speeds from the loss of stability for overly inflated shapes. |

Coverage:

|

Abstract: Flowing air and water are persistent sculptors, gradually working stone, clay, sand and ice into landforms and landscapes. The evolution of shape results from a complex fluid–solid coupling that tends to produce stereotyped forms, and this morphology offers important clues to the history of a landscape and its development. Claudin et al. (J. Fluid Mech., vol. 832, 2017, R2) shed light on how we might read the rippled and scalloped patterns written into dissolving or melting solid surfaces by a flowing fluid. By better understanding the genesis of these patterns, we may explain why they appear in different natural settings, such as the walls of mineral caves dissolving in flowing water, ice caves in wind, and melting icebergs. |

|

Abstract: The swimming direction of biological or artificial microscale swimmers tends to be randomised over long time-scales by thermal fluctuations. Bacteria use various strategies to bias swimming behaviour and achieve directed motion against a flow, maintain alignment with gravity or travel up a chemical gradient. Herein, we explore a purely geometric means of biasing the motion of artificial nanorod swimmers. These artificial swimmers are bimetallic rods, powered by a chemical fuel, which swim on a substrate printed with teardrop-shaped posts. The artificial swimmers are hydrodynamically attracted to the posts, swimming alongside the post perimeter for long times before leaving. The rods experience a higher rate of departure from the higher curvature end of the teardrop shape, thereby introducing a bias into their motion. This bias increases with swimming speed and can be translated into a macroscopic directional motion over long times by using arrays of teardrop-shaped posts aligned along a single direction. This method provides a protocol for concentrating swimmers, sorting swimmers according to different speeds, and could enable artificial swimmers to transport cargo to desired locations. |

|

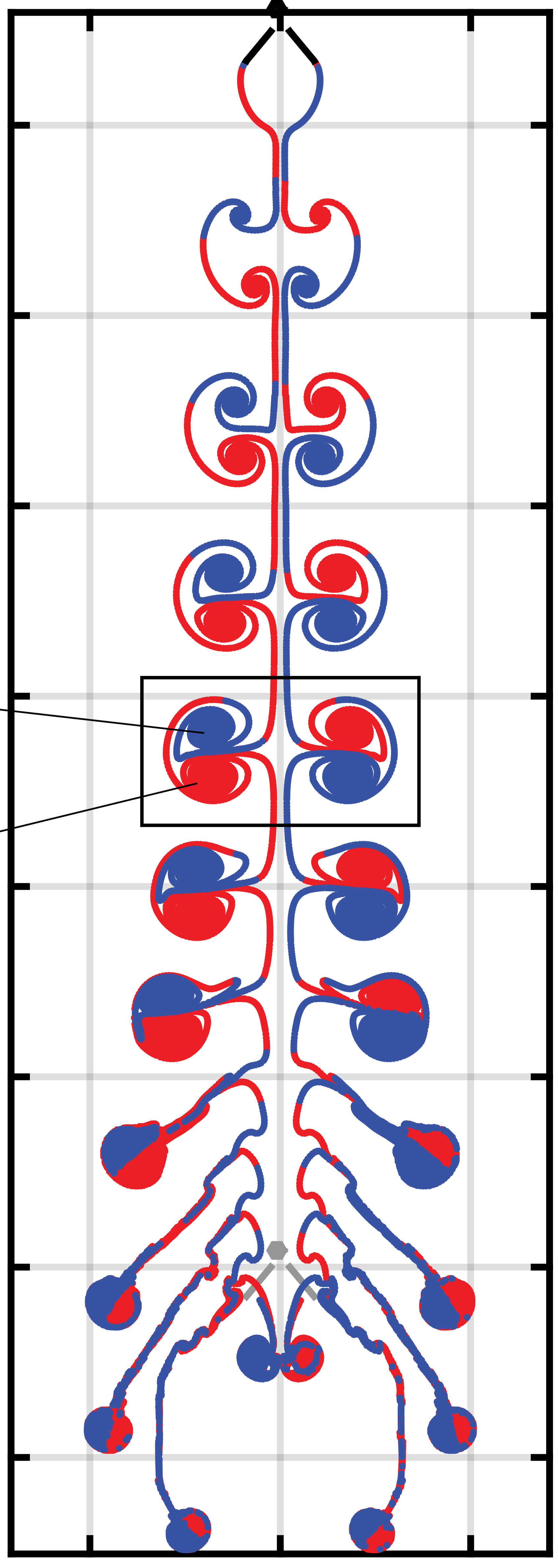

Abstract: We explore theoretically the aerodynamics of a recently fabricated jellyfish-like flying machine (Ristroph & Childress, J. R. Soc. Interface, vol. 11 (92), 2014, 20130992). This experimental device achieves flight and hovering by opening and closing opposing sets of wings. It displays orientational or postural flight stability without additional control surfaces or feedback control. Our model ‘machine’ consists of two mirror-symmetric massless flapping wings connected to a volumeless body with mass and moment of inertia. A vortex sheet shedding and wake model is used for the flow simulation. Use of the fast multipole method allows us to simulate for long times and resolve complex wakes. We use our model to explore the design parameters that maintain body hovering and ascent, and investigate the performance of steady ascent states. We find that ascent speed and efficiency increase as the wings are brought closer, due to a mirror-image ‘ground-effect’ between the wings. Steady ascent is approached exponentially in time, which suggests a linear relationship between the aerodynamic force and ascent speed. We investigate the orientational stability of hovering and ascent states by examining the flyer’s free response to perturbation from a transitory external torque. Our results show that bottom-heavy flyers (centre of mass below the geometric centre) are capable of recovering from large tilts, whereas the orientation of the top-heavy flyers diverges. These results are consistent with the experimental observations in Ristroph & Childress (J. R. Soc. Interface, vol. 11 (92), 2014, 20130992), and shed light upon future designs of flapping-wing micro aerial vehicles that use jet-based mechanisms. |

|

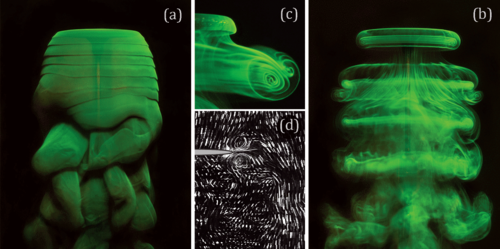

Abstract: An object immersed in a fast flow typically experiences fluid forces that increase with the square of speed. Here we explore how this high-Reynolds-number force-speed relationship is affected by unsteady motions of a body. Experiments on disks that are driven to oscillate while progressing through air reveal two distinct regimes: a conventional quadratic relationship for slow oscillations and an anomalous scaling for fast flapping in which the time-averaged drag increases linearly with flow speed. In the linear regime, flow visualization shows that a pair of counterrotating vortices is shed with each oscillation and a model that views a train of such dipoles as a momentum jet reproduces the linearity. We also show that appropriate scaling variables collapse the experimental data from both regimes and for different oscillatory motions into a single drag-speed relationship. These results could provide insight into the aerodynamic resistance incurred by oscillating wings in flight and they suggest that vibrations can be an effective means to actively control the drag on an object. |

Coverage:

|

Abstract: Classic models of fish schools and flying formations of birds are built on the hypothesis that the preferred locations of an individual are determined by the flow left by its upstream neighbor. Lighthill posited that arrangements may in fact emerge passively from hydro- or aerodynamic interactions, drawing an analogy to the formation of crystals by intermolecular forces. Here, we carry out physical experiments aimed at testing the Lighthill conjecture and find that self-propelled flapping wings spontaneously assume one of multiple arrangements due to flow interactions. Wings in a tandem pair select the same forward speed, which tends to be faster than a single wing, while maintaining a separation distance that is an integer multiple of the wavelength traced out by each body. When perturbed, these locomotors robustly return to the same arrangement, and direct hydrodynamic force measurements reveal springlike restoring forces that maintain group cohesion. We also use these data to construct an interaction potential, showing how the observed positions of the follower correspond to stable wells in an energy landscape. Flow visualization and vortex-based theoretical models reveal coherent interactions in which the follower surfs on the periodic wake left by the leader. These results indicate that, for the high-Reynolds-number flows characteristic of schools and flocks, collective locomotion at enhanced speed and in orderly formations can emerge from flow interactions alone. If true for larger groups, then the view of collectives as ordered states of matter may prove to be a useful analogy. |

|

Abstract: Biological systems often involve the self-assembly of basic components into complex and functioning structures. Artificial systems that mimic such processes can provide a well-controlled setting to explore the principles involved and also synthesize useful micromachines. Our experiments show that immotile, but active, components self-assemble into two types of structure that exhibit the fundamental forms of motility: translation and rotation. Specifically, micron-scale metallic rods are designed to induce extensile surface flows in the presence of a chemical fuel; these rods interact with each other and pair up to form either a swimmer or a rotor. Such pairs can transition reversibly between these two configurations, leading to kinetics reminiscent of bacterial run-and-tumble motion. |

|

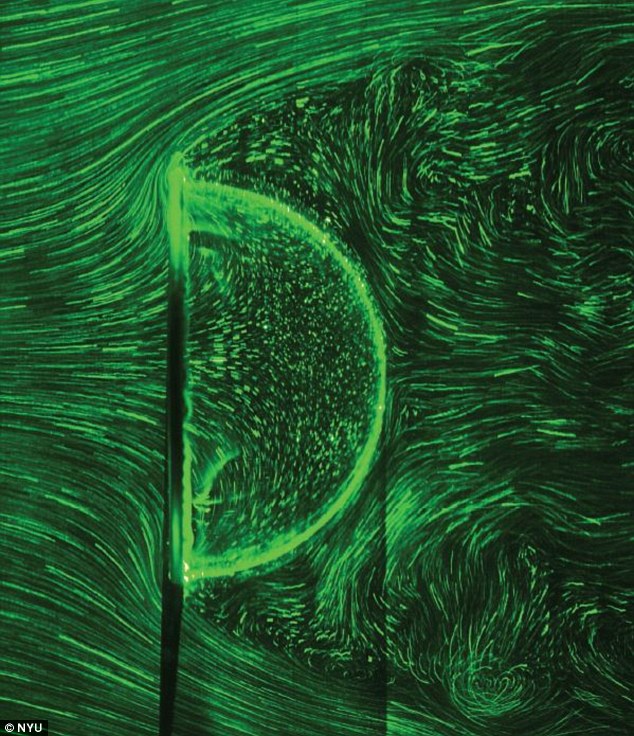

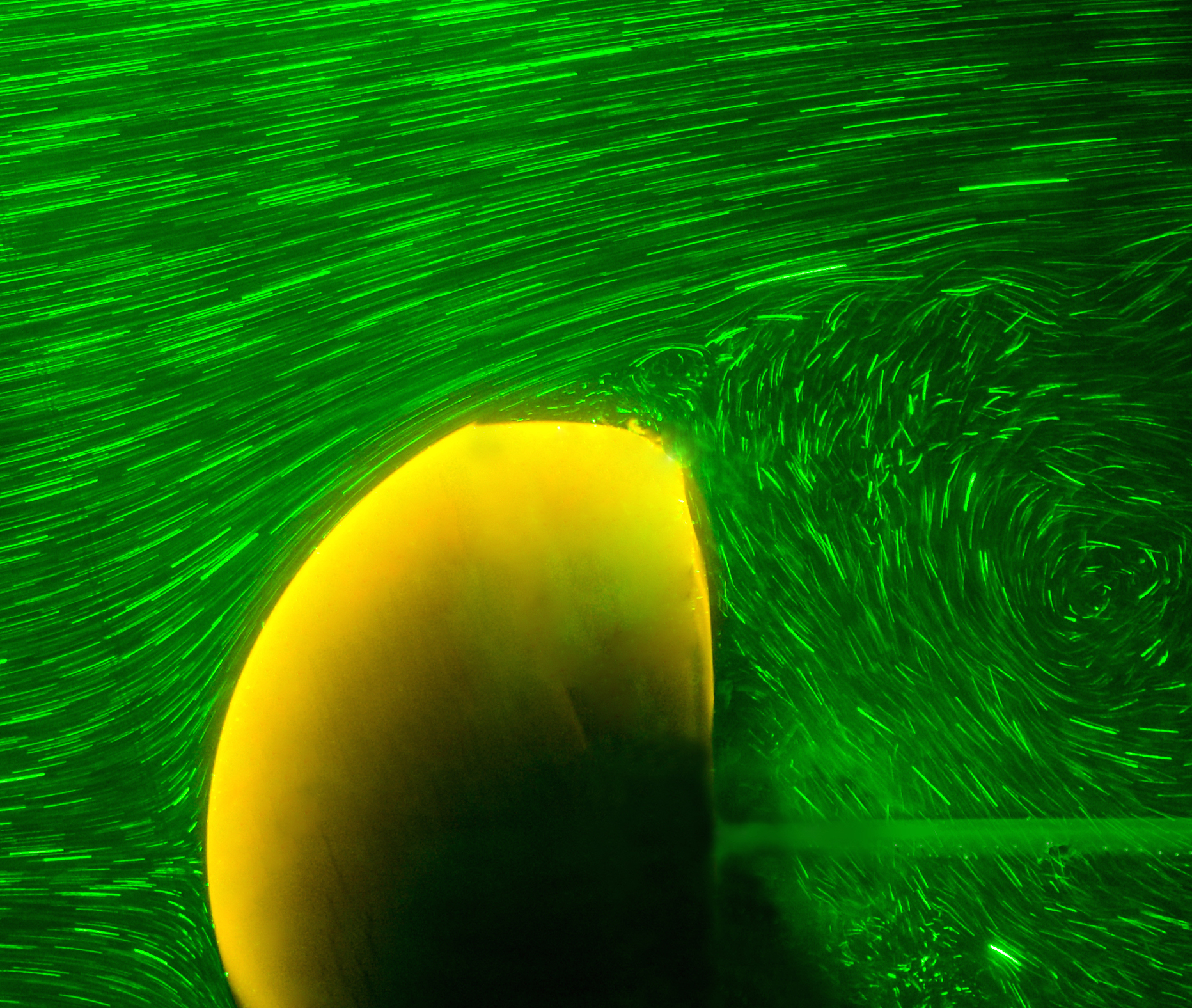

Abstract: Flow visualization is indispensable for experiments related to unsteady fluid flows, as it can reveal the subtle fluid-structure interactions that lie behind complex phenomena. Visualization also serves as an instructive way to compare unsteady or time-dependent motions of a body through a fluid to the better-characterized case of steady motion. We explore this comparison in the context of high Reynolds number (Re ∼ 104) flows past stationary and oscillating disks. A stationary disk generates an unsteady downstream wake where the flow has separated from the disk edge. By driving the disk to oscillate in-line with the oncoming current, we directly impose unsteadiness and strongly modify the separated flow. |

|

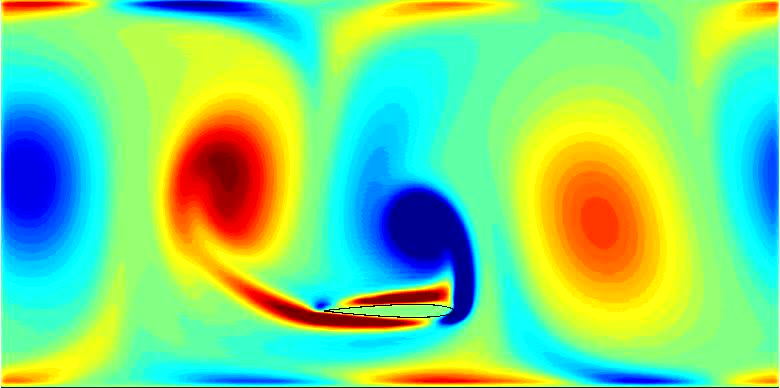

Abstract: Fish schools and bird flocks are fascinating examples of collective behaviours in which many individuals generate and interact with complex flows. Motivated by animal groups on the move, here we explore how the locomotion of many bodies emerges from their flow-mediated interactions. Through experiments and simulations of arrays of flapping wings that propel within a collective wake, we discover distinct modes characterized by the group swimming speed and the spatial phase shift between trajectories of neighbouring wings. For identical flapping motions, slow and fast modes coexist and correspond to constructive and destructive wing–wake interactions. Simulations show that swimming in a group can enhance speed and save power, and we capture the key phenomena in a mathematical model based on memory or the storage and recollection of information in the flow field. These results also show that fluid dynamic interactions alone are sufficient to generate coherent collective locomotion, and thus might suggest new ways to characterize the role of flows in animal groups. |

Coverage:

|

Abstract: The lateral line of fish includes the canal subsystem that detects hydrodynamic pressure gradients and is thought to be important in swimming behaviors such as rheotaxis and prey tracking. Here, we explore the hypothesis that this sensory system is concentrated at locations where changes in pressure are greatest during motion through water. Using high-fidelity models of rainbow trout, we mimic the flows encountered during swimming while measuring pressure with fine spatial and temporal resolution. The variations in pressure for perturbations in body orientation and for disturbances to the incoming stream are seen to correlate with the sensory network. These findings support a view of the lateral line as a “hydrodynamic antenna” that is configured to retrieve flow signals and also suggest a physical explanation for the nearly universal sensory layout across diverse species. |

Coverage:

|

Abstract: While fluid flows are known to promote dissolution of materials, such processes are poorly understood due to the coupled dynamics of the flow and the receding surface. We study this moving boundary problem through experiments in which hard candy bodies dissolve in laminar high-speed water flows. We find that different initial geometries are sculpted into a similar terminal form before ultimately vanishing, suggesting convergence to a stable shape–flow state. A model linking the flow and solute concentration shows how uniform boundary-layer thickness leads to uniform dissolution, allowing us to obtain an analytical expression for the terminal geometry. Newly derived scaling laws predict that the dissolution rate increases with the square root of the flow speed and that the body volume vanishes quadratically in time, both of which are confirmed by experimental measurements. |

Coverage:

|

Abstract: Ornithopters, or flapping-wing aircraft, offer an alternative to helicopters in achieving manoeuvrability at small scales, although stabilizing such aerial vehicles remains a key challenge. Here, we present a hovering machine that achieves self-righting flight using flapping wings alone, without relying on additional aerodynamic surfaces and without feedback control. We design, construct and test-fly a prototype that opens and closes four wings, resembling the motions of swimming jellyfish more so than any insect or bird. Measurements of lift show the benefits of wing flexing and the importance of selecting a wing size appropriate to the motor. Furthermore, we use highspeed video and motion tracking to show that the body orientation is stable during ascending, forward and hovering flight modes. Our experimental measurements are used to inform an aerodynamic model of stability that reveals the importance of centre-of-mass location and the coupling of body translation and rotation. These results show the promise of flapping-flight strategies beyond those that directly mimic the wing motions of flying animals. | |

| Presented at: Hovering of a jellyfish-like flying machine, 66th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Fluid Dynamics, November 24, 2013 | ||

Coverage:

|

Abstract: Flying insects have evolved sophisticated sensory–motor systems, and here we argue that such systems are used to keep upright against intrinsic flight instabilities. We describe a theory that predicts the instability growth rate in body pitch from flapping-wing aerodynamics and reveals two ways of achieving balanced flight: active control with sufficiently rapid reactions and passive stabilization with high body drag. By glueing magnets to fruit flies and perturbing their flight using magnetic impulses, we show that these insects employ active control that is indeed fast relative to the instability. Moreover, we find that fruit flies with their control sensors disabled can keep upright if high-drag fibres are also attached to their bodies, an observation consistent with our prediction for the passive stability condition. Finally, we extend this framework to unify the control strategies used by hovering animals and also furnish criteria for achieving pitch stability in flapping-wing robots. |

Coverage:

|

Abstract: Erosion of solid material by flowing fluids plays an important role in shaping land-forms, and in this natural context is often dictated by processes of high complexity. Here, we examine the coupled evolution of solid shape and fluid flow within the idealized setting of a cylindrical body held against a fast, unidirectional flow, and eroding under the action of fluid shear stress. Experiments and simulations both show self-similar evolution of the body, with an emerging quasi-triangular geometry that is an attractor of the shape dynamics. Our fluid erosion model, based on Prandtl boundary layer theory, yields a scaling law that accurately predicts the body's vanishing rate. Further, a class of exact solutions provides a partial prediction for the body's terminal form as one with a leading surface of uniform shear stress. Our simulations show this predicted geometry to emerge robustly from a range of different initial conditions, and allow us to explore its local stability. The sharp, faceted features of the terminal geometry defy the intuition of erosion as a globally smoothing process. |

|

Abstract: Erosion by flowing fluids carves striking landforms on Earth and also provides important clues to the past and present environments of other worlds. In these processes, solid boundaries both influence and are shaped by the surrounding fluid, but the emergence of morphology as a result of this interaction is not well understood. Here, we study the coevolution of shape and flow in the context of erodible bodies molded from clay and immersed in fast flowing water. Though commonly viewed as a smoothing process, we find that erosion sculpts pointed and corner-like features that persist as the solid shrinks. We explain these observations using flow visualization and a fluid mechanical model in which the local shear stress dictates the rate of material removal. Experiments and simulations show that this interaction ultimately leads to self-similarly receding boundaries and a unique front surface characterized by nearly uniform shear stress. This tendency toward conformity of stress offers a principle for understanding erosion in more complex geometries and flows, such as those present in nature. |

|

Abstract: We explore the stability of flapping flight in a model system that consists of a pyramid-shaped object hovering in a vertically oscillating airflow. Such a flyer not only generates sufficient aerodynamic force to keep aloft but also robustly maintains balance during free flight. Flow visualization reveals that both weight support and orientational stability result from the periodic shedding of vortices. We explain these findings with a model of the flight dynamics, predict increasing stability for higher center of mass, and verify this counterintuitive fact by comparing top- and bottom-heavy flyers. |

Coverage:

|

Note: This work was selected by Physics Today and published in the section "Back Scatter." |

|

Abstract: Complex behaviors of flying insects require interactions among sensory-neural systems, wing actuation biomechanics, and flapping-wing aerodynamics. Here, we review our recent progress in understanding these layers for maneuvering and stabilization flight of fruit flies. Our approach combines kinematic data from flying insects and aerodynamic simulations to distill reduced-order mathematical models of flight dynamics, wing actuation mechanisms, and control and stabilization strategies. Our central findings include: (1) During in-flight turns, fruit flies generate torque by subtly modulating wing angle of attack, in effect paddling to push off the air; (2) These motions are generated by biasing the orientation of a biomechanical brake that tends to resist rotation of the wing; (3) A simple and fast sensory-neural feedback scheme determines this wing actuation and thus the paddling motions needed for stabilization of flight heading against external disturbances. These studies illustrate a powerful approach for studying the integration of sensory-neural feedback, actuation, and aerodynamic strategies used by flying insects. |

|

Abstract: By analyzing high-speed video of the fruit fly, we discover a swimminglike mode of forward flight characterized by paddling wing motions. We develop a new aerodynamic analysis procedure to show that these insects generate drag-based thrust by slicing their wings forward at low angle of attack and pushing backwards at a higher angle. Reduced-order models and simulations reveal that the law for flight speed is determined by these wing motions but is insensitive to material properties of the fluid. Thus, paddling is as effective in air as in water and represents a common strategy for propulsion through aquatic and aerial environments. |

|

Abstract: Just as the Wright brothers implemented controls to achieve stable airplane flight, flying insects have evolved behavioral strategies that ensure recovery from flight disturbances. Pioneering studies performed on tethered and dissected insects demonstrate that the sensory, neurological, and musculoskeletal systems play important roles in flight control. Such studies, however, cannot produce an integrative model of insect flight stability because they do not incorporate the interaction of these systems with free-flight aerodynamics. We directly investigate control and stability through the application of torque impulses to freely flying fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) and measurement of their behavioral response. High-speed video and a new motion tracking method capture the aerial “stumble,” and we discover that flies respond to gentle disturbances by accurately returning to their original orientation. These insects take advantage of a stabilizing aerodynamic influence and active torque generation to recover their heading to within 2° in <60 ms. To explain this recovery behavior, we form a feedback control model that includes the fly’s ability to sense body rotations, process this information, and actuate the wing motions that generate corrective aerodynamic torque. Thus, like early man-made aircraft and modern fighter jets, the fruit fly employs an automatic stabilization scheme that reacts to short time-scale disturbances. |

|

Abstract: Flying insects execute aerial maneuvers through subtle manipulations of their wing motions. Here, we measure the free-flight kinematics of fruit flies and determine how they modulate their wing pitching to induce sharp turns. By analyzing the torques these insects exert to pitch their wings, we infer that the wing hinge acts as a torsional spring that passively resists the wing’s tendency to flip in response to aerodynamic and inertial forces. To turn, the insects asymmetrically change the spring rest angles to generate asymmetric rowing motions of their wings. Thus, insects can generate these maneuvers using only a slight active actuation that biases their wing motion. |

|

Abstract: Flying insects perform aerial maneuvers through slight manipulations of their wing motions. Because such manipulations in wing kinematics are subtle, a reliable method is needed to properly discern consistent kinematic strategies used by the insect from inconsistent variations and measurement error. Here, we introduce a novel automated method that accurately extracts full, 3D body and wing kinematics from high-resolution films of free-flying insects. This method combines visual hull reconstruction, principal components analysis, and geometric information about the insect to recover time series data of positions and orientations. The technique has small, well-characterized errors of under 3 pixels for positions and 5 deg. for orientations. To show its utility, we apply this motion tracking to the flight of fruit flies, Drosophila melanogaster. We find that fruit flies generate sideways forces during some maneuvers and that strong lateral acceleration is associated with differences between the left and right wing angles of attack. Remarkably, this asymmetry can be induced by simply altering the relative timing of flips between the right and left wings, and we observe that fruit flies employ timing differences as high as 10% of a wing beat period while accelerating sideways at 40% g. |

|

Abstract: In aggregates of objects moving through a fluid, bodies downstream of a leader generally experience reduced drag force. This conventional drafting holds for objects of fixed shape, but interactions of deformable bodies in a flow are poorly understood, as in schools of fish. In our experiments on ``schooling" flapping flags we find that it is the leader of a group who enjoys a significant drag reduction (of up to 50 %), while the downstream flag suffers a drag increase. This counterintuitive inverted drag relationship is rationalized by dissecting the mutual influence of shape and flow in determining drag. Inverted drafting has never been observed with rigid bodies, apparently due to the inability to deform in response to the altered flow field of neighbors. |

Coverage: